When Angela Skelton left an abusive relationship about 12 years ago, she moved to Fort Wayne to live with her parents.

Since then, sometimes working three jobs at a time, she’s managed to save enough money to move into a two-bedroom apartment with two of her children. But when her rent went up $300 a month in late 2019 and her third son moved home at the beginning of the pandemic, they needed more space.

That commenced an apartment hunt in Fort Wayne, which Skelton says lasted nearly two years.

‘It felt like another job,” she says. “As the price of rent goes up and the number of houses available goes down, it’s getting harder and harder to find somewhere to live.”

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began—and even before it—finding and maintaining stable housing has been challenging for many families in Fort Wayne and across the U.S. For single mothers, the issue is compounded by factors, like the need for additional bedrooms, the liability of renting with children, and the cost of childcare, just to name a few.

Vincent Village, Inc., is a transitional shelter in Allen County that serves homeless families with children. Its campus at 2827 Holton Ave. in Fort Wayne includes a shelter, as well as two duplexes and 32 free-standing homes rented to residents at affordable rates.

While the shelter includes housing for two-parent families and single-male-headed families, Executive Director Sharon Tucker says the Village is seeing more mothers and single mothers, in particular, become unsheltered than ever before. Currently, all families in its emergency shelter are single mothers, and throughout the Village, 90 percent are single mothers.

“That number fluctuates, of course,” Tucker says. “But we’re always about a 6-to-1 ratio of mothers compared to fathers and/or couples, and many single mothers are unhoused because they’re escaping domestic violence. Single mothers are also at greater risk of being unsheltered because of the multitude of barriers they have to face as opposed to family units, where one spouse can stay home while the other works. Single parents don’t have that option.”

Skelton says her family and social network have been critical to her journey to build a life for herself and her children in Fort Wayne. In her day job, she works for Indiana’s Division of Family Resources, which approves peoples’ eligibility for programs like Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Like Tucker, she sees many mothers and families facing housing insecurity who don’t have access to social networks like hers to fall back on.

In fact, having trustworthy connections is the only way she’s been able to find and afford housing. Today, she shares a three-bedroom apartment at Archer’s Pointe with her boyfriend, who has two children of his own. She says if she was still apartment hunting on her own, as a single parent, the search “would be impossible.” That’s because, in addition to affording her monthly rent, which is about $1,440 including utilities, most apartments also require renters to have good credit histories, to make security deposits, and to have enough personal income to cover two or three times their monthly rent upfront—or to find a cosigner who can.

“My partner and I both earn enough to afford the monthly rent on our own, but we don’t make three times our monthly rent to get the apartment without combining our incomes,” Skelton says.

Her situation speaks to a widening affordability gap families across the U.S. are facing when it comes to housing and inflation. Skelton and her partner each earn too much money to qualify for housing assistance. But that doesn’t mean they can live comfortably—even in an “affordable” city like Fort Wayne. In their apartment, they have a triple bunk bed in one bedroom for the girls and another bunk bed in the second bedroom for the boys.

“We’re living on top of each other,” Skelton says.

She’s encountered misconceptions about the affordability of Fort Wayne’s housing market, too.

“Sometimes, people say, ‘Buying a house is more affordable than renting, so why don’t you just buy a house?’” Skelton says. “Trust me, if I had the credit and the money to make a down payment on a house, I would, and I could actually be saving money in the long run.”

In her housing search, she’s seen three-bedroom homes in Fort Wayne with monthly mortgage rates between $700-900. These would give her family more space and stability than their apartment—and would cost about half the price each month. But barriers like credit and down payments keep her and her partner at bay, trapped in a cycle of renting, and in the long run, paying more than it would cost them to own.

“Rental payments and mortgage payments in Fort Wayne really don’t coincide with each other,” Skelton says. “When you can’t get past that barrier to homeownership, it’s very frustrating.”

In many ways, Vincent Village’s shelter and rental structure are designed to help families scale barriers to housing access and become self-sufficient. The Village helps families find jobs and ways to pay off debt, budget, and improve their credit scores. As families earn money, they can rent one of the Village’s units, starting at $250 a month for those earning less than 30 percent of the area median income, and progress up to rental homes for about $700 a month.

“The increase is designed to help clients adjust to what rent would be without our support as they transition to independence,” Tucker says.

The problem is, beyond the Village’s borders, affordable rental units at 30 percent of the area median income (AMI) are getting harder and harder to find in Fort Wayne. Tucker calls them “almost nonexistent.”

She clarifies that providing “affordable housing” doesn’t necessarily require landlords to accept Section 8 vouchers.

“It might just mean offering housing that’s $700 a month, or 30 percent of the AMI, which is considered ‘affordable,’ without being Section 8,” she says.

But in Fort Wayne’s rental scene, even these prices are difficult to come by, particularly for the multiple-bedroom units parents need.

“Many landlords have come to realize it’s a hot market for them, so investors outside of the community are purchasing units, independent structures, or apartment complexes and opting to not accept vouchers or to offer affordable housing anymore,” Tucker says. “That puts an amazing downward pressure on people already earning a minimum wage, or low wages.”

Currently, a minimum wage of $17 an hour is what’s needed for a family of two to not fall through the cracks as part of the ALICE (Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed) population of those who are working, yet not able to afford basic necessities. On top of that, mothers have compounding challenges, like the high cost of childcare in the U.S.

“You add the expense of $1,200 a month for childcare with the $935 a month for rent on a three bedroom apartment, and that’s $2,100 a month a mom would need to earn just for two required necessities,” Tucker says.

To help families sidestep expensive rentals and become homeowners, Tucker has talked with a few local banks about establishing partnerships and programs that could help families secure loans for smaller amounts of money. That way, they could purchase within their budget and build equity, rather than being forced to rent.

“If we could help folks become homeowners, then those who have been struggling to make rental payments for $1,000 a month could potentially get mortgages for $300 a month, and right there, we’ve created $700 a month of wealth for them,” Tucker says. “Those are ways we, as a community, could break the cycle to help individuals.”

Until homeownership is more accessible, many families are stuck renting and making high monthly payments. And under Indiana’s disproportionate landlord-friendly laws, that means higher chances of eviction.

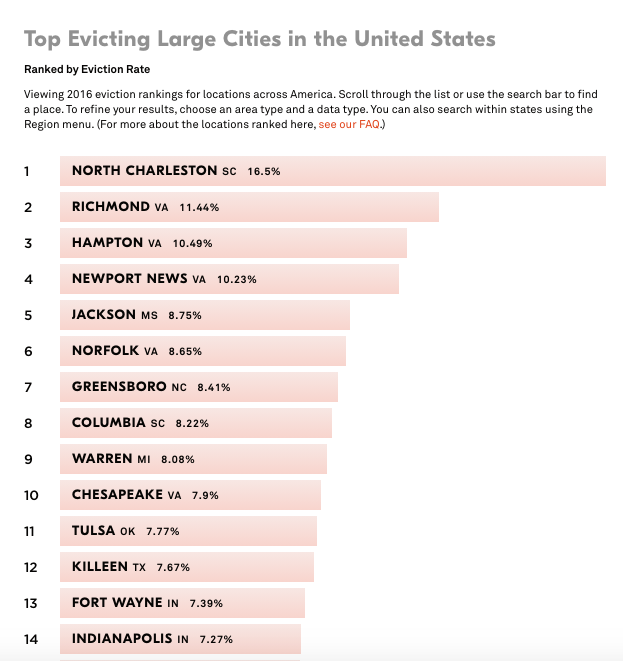

Before COVID-19 began, Fort Wayne had the 13th highest eviction rate in the U.S., and conditions have only gotten more challenging as inflation has increased and the housing market has heated up.

Data from Eviction Lab shows that even during Indiana’s moratorium from March 19-Aug. 14, 2020, statewide eviction filings surpassed 170 in April, 400 in May, and were upward of 850 in both June and July.

Andrew Thomas is an attorney with Indiana Legal Services, Inc (ILS), a clinic that offers cost-free, on-site legal counsel and representation to tenants facing evictions at the Allen County Courthouse. He’s participating in a Tenant Assistance Legal Clinic in partnership with the City of Fort Wayne’s Housing and Neighborhood Services and other local groups, like Just Neighbors.

In April, Thomas said the clinic had served more than 500 families, noting the majority of his clients identify as single, African-American women who are the heads of their households.

Another organization helping moms and children avoid and deal with evictions is a cost-free crisis helpline in Northeast Indiana called New Mercies Ministries. Executive Director Bonnie Doolittle says about 60 percent of the people her ministry serves are moms who are either facing an eviction, already evicted and couch surfing, or struggling to manage housing on their own.

New Mercies Ministries utilizes a network of more than 50 background-checked, volunteer church families to give moms in crisis a place to find safe, temporary housing for their children. At the same time, its staff, family coaches, and volunteers walk alongside moms as trustworthy friends, helping them through whatever crisis they are facing.

“We have seen an increase of parents calling us since the pandemic began, with an increase from 50 percent to 60 percent being moms already being evicted, trying to find money to avoid an eviction, or recovering from an eviction,” Doolittle says. “Because once you’ve been evicted, it’s even harder to rent again.”

“That’s a situation we’re facing today,” Doolittle adds. “We just got a call from a mom with three children who have nowhere to sleep tonight because they’re being evicted again.”

Doolittle’s team consists of seven staff, three full-time and four part-time, who work all-hands-on-deck, making calls for families as needs arise. They often fill gaps for moms between other shelters and housing services, like Vincent Village, A Mothers Hope, and St Joseph Missions Women’s Shelter. They have 158 volunteers in their own regional network, too, including host families, family coaches, and service providers, like childcare workers or drivers for families.

“So far, we’ve done 302 hostings, serving 55 families and 86 children, just this year,” Doolittle says in mid-July.

New Mercies Ministries supplies its volunteers with almost everything they need to support children, like formula and car seats. These resources, as well as the organization’s staff, are funded by grants from groups, like St. Joseph Community Health Foundation.

By coordinating multiple needs and services with families, Doolittle’s team provides highly personalized support to help them stabilize and reunify as soon as possible.

“Our goal is to provide extended-family-like support,” Doolittle says. “But when you have a problem, you might call your sister or your mom, and she helps you. That’s what we can provide.”

The value of these services speaks the underlying importance of connection in cities and how disconnection—or being cut off from resources, as well as from trustworthy people and opportunities—traps individuals and families in cycles of poverty and abuse.

That’s why it’s not just a matter of making housing more affordable and available to low-income residents, Tucker says, but also finding ways to create stronger, more integrated social networks in Fort Wayne. This often entails including people of different income levels and backgrounds in the same streets and apartment complexes, where they can encounter each other as neighbors.

“It’s about not concentrating poverty in one area, but spreading the opportunity for people to live in communities where they choose to live and where there is no segregation based on low-income housing,” Tucker says. “It’s been my experience that the majority of families coming to us and needing help at Vincent Village, ultimately need one thing many of us have in Fort Wayne: That’s a network.”

Doolittle says, on average, American adults experience about two crises per year. When those events come up, many of us scroll through our contact list for the names of those one or two people we can call—people we rely on to help us no matter what.

When you live in poverty—and oftentimes isolated, generational poverty—you don’t have those contacts.

“Ninety-nine percent of the moms we serve open their phones, and see no one they can trust,” she says.

This story is underwritten by support from St. Joseph Community Health Foundation. It is also part of a series on Solutions emerging during the COVID-19 pandemic, underwritten by Brightpoint.

This article is distributed in partnership with the Fort Wayne Media Collaborative, a group of media outlets and educational institutions in Fort Wayne committed to solutions-oriented reporting. More information is available at fwmediacollaborative.com.