Like most places in the United States, Fort Wayne was largely built by people who immigrated from their homes to a new land. European control of Fort Wayne began with the French, then the British, and finally the Americans. The Miami had settled here prior to and lived here during European settlement, and little is known about groups who lived here prior to the Miami.

After the Americans had secured the area around the confluence of the three rivers, the land opened for settlement by various ethnic groups stemming from Europe. While this immigration and population growth was dominated by the Germans for several decades, several other groups from around the world also played an important role in the building of Fort Wayne as it stands today.

According to the Allen County Genealogical Society of Indiana (ACGSI), orders went out from French Canada in 1719 and 1720 ordering fur traders to trade with the Miami who lived in the area of the confluence of the three rivers. This area had been occupied for hundreds, if not thousands of years by subsequent groups of Native Americans. The most recent, the Miami, maintain a presence in present-day Fort Wayne. One historian asserted in an early 20th Century volume that human presence in the area even predates the three rivers.

The French and the Miami joined in fighting against the British during the French and Indian War, with the British finding themselves victorious in 1763. While the loss of the French and Miami gave way for British control over the area, the British declared in 1763 that no one would settle west of the Appilatian divide, which protected the Miami village of Kekionga from settlement by the British. The Miami village remained under the hands-off control of the British until the Americans won the Revolutionary War and the British ceded their claims to present-day Indiana in 1783. Through this time, the Miami continued living at the confluence of the three rivers.

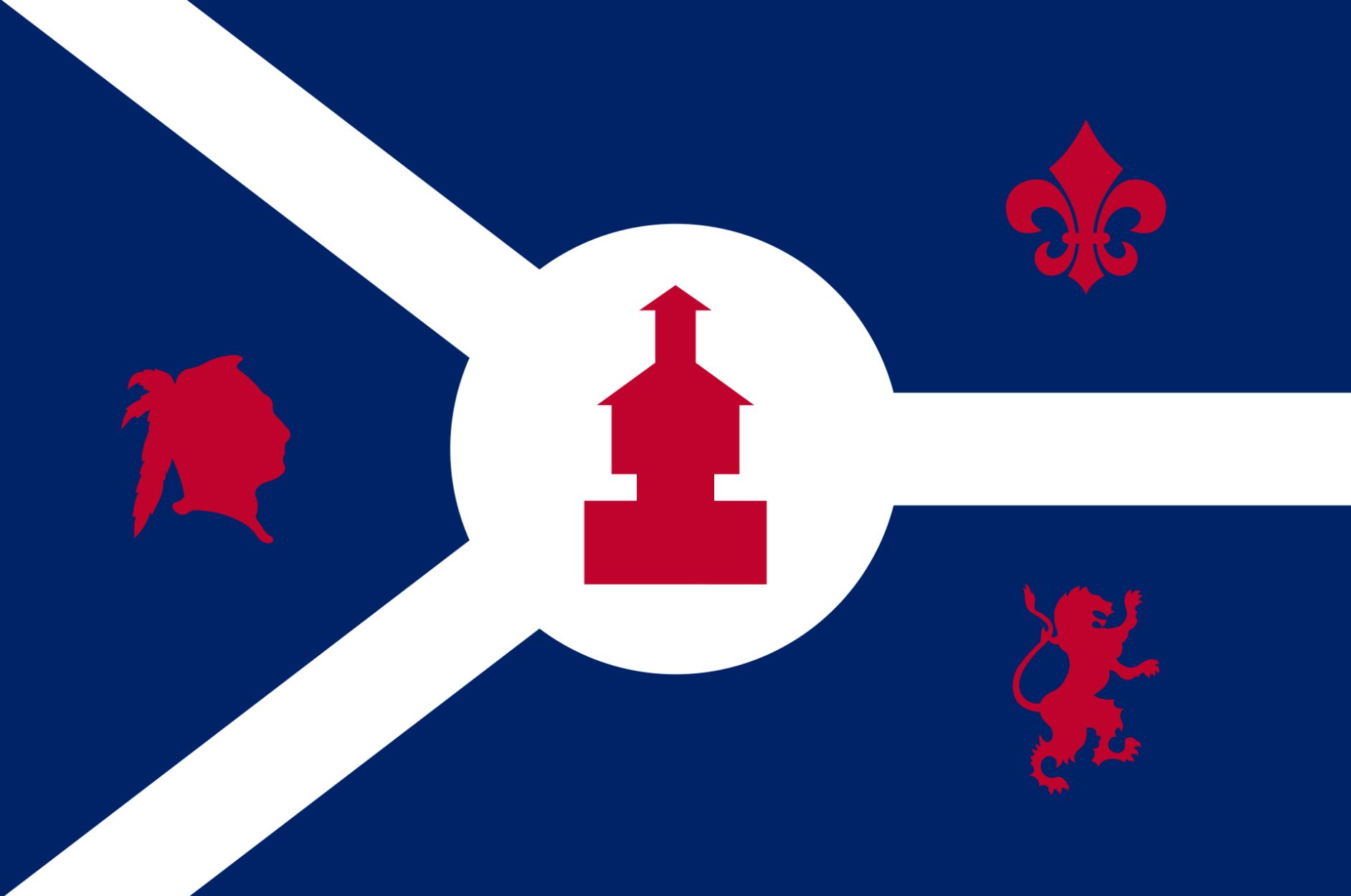

This period of history between the French, Miami, British and Americans was immortalized in the city flag of Fort Wayne. The fleur-de-lis represents France, the Native American head represents the Miami, the lion represents the British and the fort represents the Americans.

In 1823 two businessmen, John T. Barr and John McCorkle purchased a section of land below the St. Mary’s River. Over the years this land was sold to various settlers, and waves of immigrants started to settle the area as well. The Miami were ordered to leave in 1846.

A wave of German immigrants came to Fort Wayne shortly after lots had come up for sale. The predominant immigrant who cleared the way for this German settlement was Henry Rudisill, who was memorialized with a major city street named for him. After the Lutheran Church had been established in Fort Wayne with the help of Rudisill, German immigrants had a cultural anchor on which to build their local community. At its peak, the German population of Fort Wayne was around 66%, and many civic leaders claimed German ancestry. However, as the United States entered World War I, German heritage was largely pushed underground. The German-American National Bank was renamed to Lincoln Bank. German newspapers shuttered, and teachers were forbidden by law to teach German to their students. As tensions around both world wars eased, so did the attitude toward the large German community in Fort Wayne. Germanfest was established in 1981 and continues to celebrate and remember German heritage in Fort Wayne today.

A wave of German immigrants came to Fort Wayne shortly after lots had come up for sale. The predominant immigrant who cleared the way for this German settlement was Henry Rudisill, who was memorialized with a major city street named for him. After the Lutheran Church had been established in Fort Wayne with the help of Rudisill, German immigrants had a cultural anchor on which to build their local community. At its peak, the German population of Fort Wayne was around 66%, and many civic leaders claimed German ancestry. However, as the United States entered World War I, German heritage was largely pushed underground. The German-American National Bank was renamed to Lincoln Bank. German newspapers shuttered, and teachers were forbidden by law to teach German to their students. As tensions around both world wars eased, so did the attitude toward the large German community in Fort Wayne. Germanfest was established in 1981 and continues to celebrate and remember German heritage in Fort Wayne today.

A large wave of Irish immigrants came to the area seeking employment during the building of the Wabash-Erie Canal. While several prominent individuals in Fort Wayne history claimed Irish heritage, this new wave was not welcomed according to a local expert. Many businesses would not employ the immigrants, but organizers of landmark infrastructure projects hired the Irish to construct the Wabash-Erie Canal and railways in the area. The Irishmen moved their families to Fort Wayne and neighboring towns, and they brought their Irish-Catholic culture with them. Several local Catholic parishes, including St. Patrick Parish in Lagro, IN, and St. Patrick Parish in Fort Wayne were both founded because of immigrating Irish families.

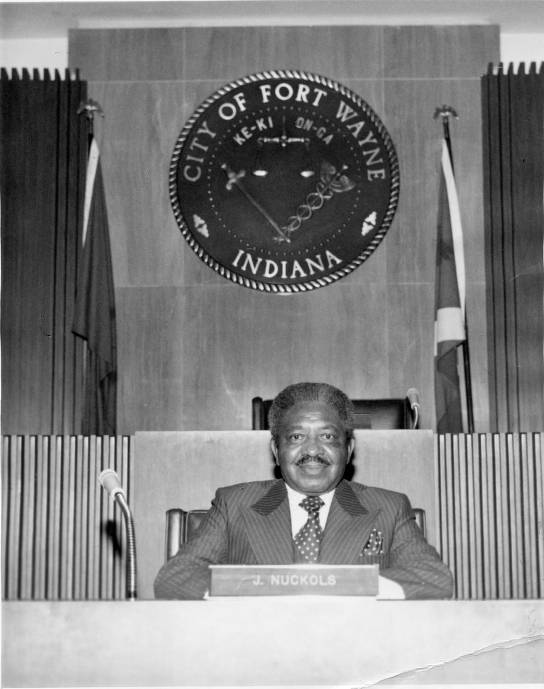

From the moment of statehood in 1816, slavery has been illegal in Indiana. However, Black Hoosiers still faced hardship. Legislation through the middle of the 19th Century prohibited African American immigration to Indiana, though the first documented people of African decent living in what is now Indiana were slaves held by French settlers. The end of the Civil War in 1865 and subsequent Great Migration decades later drove many African Americans north, with many likely settling in Fort Wayne. The first Black city councilman, John Nuckols, was elected in 1959. Today, three city council members are Black, and the council has had at least one Black member every year since Nuckols. A group parented by the MLK Jr. Club is advocating to change the name of Calhoun Street to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, due to Vice President John C. Calhoun’s views on slavery.

Over the past two decades, Fort Wayne has seen an explosion of Burmese settlement. A driving factor in the boom of Burmese immigration over the last two decades is unrest in their home country of Myanmar (formerly Burma). Civil wars and political turmoil have destabilized the nation, as well as the 2021 military coup d’etat in which the military asserted control over the country. One key player in this local resettlement has been Catholic Charities of Fort Wayne-South Bend. Nyein Chan, the director of resettlement services for the organization says that Fort Wayne is a prime city for Burmese immigrants because of the low cost of living. When compared to large cities like Indianapolis, Fort Wayne is less chaotic and is easier for the Burmese to navigate.

He says that while Fort Wayne is no longer the largest host for the resettlement of the Burmese, the local population continues to grow due to secondary immigration. This happens when someone initially settles in a different city before moving to Fort Wayne. Affordable housing options, he added, have attracted many Burmese to Fort Wayne, as well as the ease of transportation when compared to larger metro areas.

“Housing is still challenging, but relatively much cheaper than living in a bigger city.” he said, adding that many Burmese have a language barrier that may make it difficult to thrive in a large city.

Today, the ethnic makeup of Fort Wayne is still highly German, although the proportions of different groups have changed over the past several decades. According to datausa.io, 8.25% of Fort Wayne’s population in 2022 was foreign born, compared to 7.89% in the year prior. Of the forign-born residents, most came from Mexico, with India and China following. According to Zipatlas.com, those with German heritage make up 30.1% of the population, those with Black heritage make up 12.9% and Irish heritage makes up 10.6%. WBOI reported in 2016 that 6,000 Burmese lived in Fort Wayne, making up around 3.8% of the population.

Fort Wayne is more ethnically diverse today than it was at the beginning of the city, and is no longer completely dominated by a singular country of origin. Additionally, the softening of ethnic lines between citizens and neighborhoods has contributed to the lessening of outward cultural signals by individual citizens. Rather, heritage is remembered through historical markers and festivals. Despite these festive memorials, a lot of the cultural identity and history of different groups who immigrated to Fort Wayne goes unrecognized, and local community leaders and government officials are working to change that.

This article is distributed in partnership with the Fort Wayne Media Collaborative, a group of media outlets and educational institutions in Fort Wayne committed to solutions-oriented reporting. More information is available at fwmediacollaborative.com.