Language services, affordable housing and access to jobs are among the top needs of Indiana’s growing refugee population, according to a new report published this week by Indiana University researchers.

Researchers at IU’s Center for Research on Inclusion and Social Policy (CRISP) used interviews with local refugees and employees at refugee-serving agencies in Indiana to inform the report, which intends to identify service gaps and provide policy recommendations. Research analyzed throughout the policy brief shows the barriers both groups face are often intertwined.

The report follows an influx of Afghan refugees that came to Indiana last year, after escaping a country once again ruled by Taliban militants.

“It led me and my team to start thinking – what does this process of resettlement and integration here in Indiana look like? And how are the systems set up to help these individuals succeed?” said Kristi Schultz, a CRISP researcher who helped lead the study. “That’s really what sparked the interest in this topic, and for us to start taking a deeper dive into all of it.”

A census of refugees in Indiana

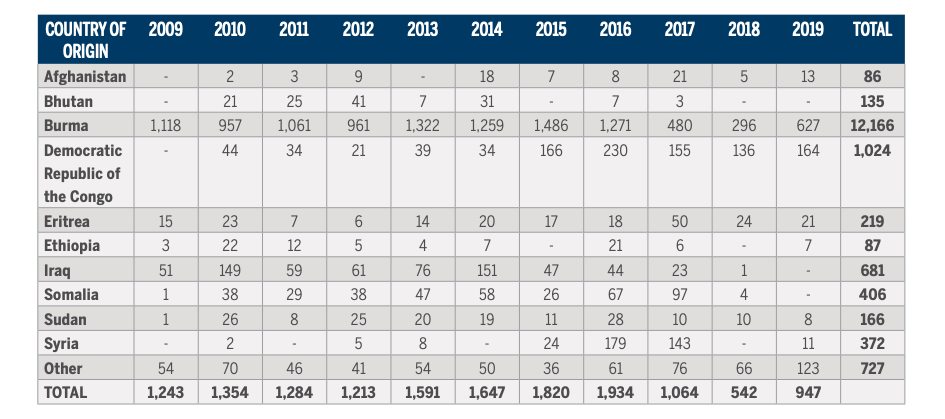

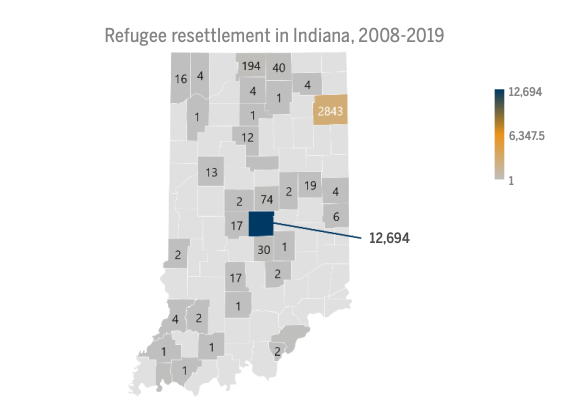

Indiana is home to approximately 27,800 resettled refugees, according to the CRISP report.

From 1970 to 2007, between 200 and 500 refugees resettled in the state each year.

The Syrian civil war led to a 63% increase in refugee arrivals in Indiana from 2011 to 2015. In 2016, 1,934 primary refugees — those who first entered the U.S. through Indiana — resettled in the state.

In the most recent count, 202 refugees arrived in Indiana between October 2020 and September 2021.

The largest refugee group in Indiana comes from Burma, accounting for more than 80% of all arrivals in the state since 2007.

More than 35,000 Burmese people now call Indiana home. Most were forced to flee Myanmar (formerly Burma) amid ongoing violence in the Southeast Asian nation.

Indianapolis is home to the largest Burmese community in the country — about 24,000 people as of 2020. Fort Wayne is home to about 10,000 Hoosiers from Burma, and smaller populations also reside in Bloomington, South Bend and Logansport.

While dozens of other nations are represented throughout Indiana, other predominant refugee groups in Indiana are from Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia, Haiti, Sudan, and Syria.

Primary refugees are generally resettled in Allen or Marion counties, which have existing refugee populations and more support resources available.

Asylum-seekers and secondary refugees — those who enter the United States elsewhere and then move to Indiana — tend to settle statewide.

Challenges upon resettlement make it harder to find jobs, housing and health care

Indiana’s refugee population encounters multiple barriers to self-sufficiency, according to the report.

That includes learning a new language, finding affordable housing, securing stable jobs, navigating health care, finding reliable transportation, and having coordinated social support systems where they live.

Researchers said a lack of language skills “impacts every area of a refugee’s experience.”

Resettlement agencies commonly provide language classes, but many people struggle to attend due to work and other responsibilities.

Refugees also often lack awareness of language options that could help with resettle. Researchers noted that refugees with low English literacy frequently fail citizenship tests because they are not aware that they can petition to have an interpreter at the interview.

Additionally, health care services that accept Medicaid or other federal financial assistance are required by law to provide an interpreter. Many providers are uninformed about that obligation.

Resettlement agencies rallied to get the state’s Bureau of Motor Vehicles to use interpreters for refugees, yet few other agencies have followed suit.

“Language is really this major barrier that’s interwoven into all of the other barriers,” Schultz said. “If you don’t have language access, or access to translations, you’re going to have a very difficult time meeting all of these other requirements.”

Other aspects of resettlement are also intertwined.

Securing a stable job may first require finding affordable housing situated on reliable public transportation routes, for instance.

Maintaining consistent employment is also difficult — especially when refugees are still learning English, or lack access to a car.

Finding health care is complex, too. Although many medical facilities are legally required to provide language assistance, refugees may not understand their rights or how to efficiently navigate those systems.

In one example, Congolese women in Indianapolis expressed confusion about multiple state- and federal-level programs, including the Healthy Indiana Plan and the local version of Medicaid. Their frustration was made worse by “cumbersome medical appointment systems” and not being able to see a doctor at crucial times.

Some women said a lack of interpreters may have contributed to their long wait times. Others believed discrimination played a role.

The COVID-19 further exacerbated other barriers to resettlement. CRISP researchers noted that low-skilled refugees are likely to have frontline jobs, which made them more vulnerable to loss of employment and health care benefits during the pandemic. Refugees were less likely during the pandemic to spend time improving their language skills, instead focussing on more basic needs like income assistance

Still, the pandemic created some new opportunities for resettlement, the most notable being online services, according to the report. Refugee agencies across the state prioritized digital access to services like digital language and citizenship classes. That made it easier for refugees to attend, without having to worry about transportation and child care.

Researchers recommend solutions

Increased government funding was a top solution identified by the CRISP team. Additional dollars can be used by resettlement agencies to hire more staff, provide additional points of contact, support refugees for longer periods of time, and support a wider scope of resettlement issues, researchers said.

More access to language services is also paramount.

Access to education and vocational training “should be a priority.” While refugees work toward English proficiency, translation services should be readily available at essential community services, including medical offices, banks, legal offices, and governmental agencies.

Those same service centers should also increase cultural sensitivity training internally to bolster trust between refugees and providers, according to the CRISP brief.

With additional funding, resettlement agencies can also better support refugees’ housing expenses while they find adequate work, and help them acquire bus passes or driver’s licenses, which the report said is “critical to self-sufficiency.”

The CRISP team also recommended that state and local leaders dive deeper into understanding their local refugee populations. They say doing so will help them discern additional cultural barriers specific to each refugee group and how to best help them acclimate to their new homes.

“I would love to see legislators really highlight those local resettlement agencies, as well as underscore the importance of the voices of the refugees that are being resettled here,” Schultz said. “They’re really the ones who can dictate or express what they need to thrive here in the Hoosier state.”

This article is distributed in partnership with the Fort Wayne Media Collaborative, a group of media outlets and educational institutions in Fort Wayne committed to solutions-oriented reporting. More information is available at fwmediacollaborative.com.